Only A Comprehensive Indo-Pacific Agreement Can Defy China’s Gravity

(Originally published on Forbes.com)

November will be heavy on pronouncements, commitments, reassurances, and the unveiling of new initiatives among countries in the Indo-Pacific region. Ground zero for this month’s activities is San Francisco, where the United States will host the annual summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and its multitude of related ministerial meetings, stakeholder convenings, and sideline huddles. The plates of governments, businesses, and NGOs are full, as the region grapples with many pressing challenges. Deftly navigating the strategic rivalry between the United States and China is one such challenge, so the possibility of warming relations resulting from a long-awaited meeting between Presidents Biden and Xi in San Francisco is welcome news to most of APEC’s 21 members. But of concrete importance to the goal of insulating regional economies from potential geopolitical fallout is the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) negotiations, certain sections of which are reportedly nearly concluded with expectations of an official announcement next week.

Following the dispiriting withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017, the governments of the IPEF’s 13 other members are pleased that the Biden administration took the initiative to formally reengage economically in the region. That engagement is expected to yield commitments that encourage cooperation, resource sharing, and cultivation of best practices in harnessing the green-energy transition, curtailing corruption, promoting labor rights, and diversifying and fortifying supply chains against natural and man-made disruptions. However, relative to previous U.S. “trade” agreements, the emerging IPEF deal is uncharacteristically tepid or plainly silent in the areas most likely to facilitate and strengthen economic integration between the United States and the Indo-Pacific.

Ever since Washington began framing its trade and technology frictions with Beijing in the context of a growing rivalry, officials from the Indo-Pacific region have been pleading with U.S. counterparts not to put them in positions where they would be forced to choose between the United States and China. Understandably, countries such as New Zealand, Singapore, and South Korea would prefer the bounty of deep, unimpeded engagement with the world’s two largest economies rather than favor one and court the wrath of the other. But as Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said in response to this concern: “We’re not asking people to choose; we want to give [them] a choice. And that means we have to have something to put on the table.” Exactly.

Just as most Americans expect turkey to be the featured dish on Thanksgiving, U.S. partners in the Indo-Pacific – and U.S. exporters to the region – expect improved access to markets to be the main course on their trade agreement tables. Although the IPEF contains some innovations that address legitimate, regional concerns, the complete absence of tariff commitments and the Biden administration’s very recent abandonment of support for rules governing digital trade policies are likely to render the initiative far less consequential than it could and should be.

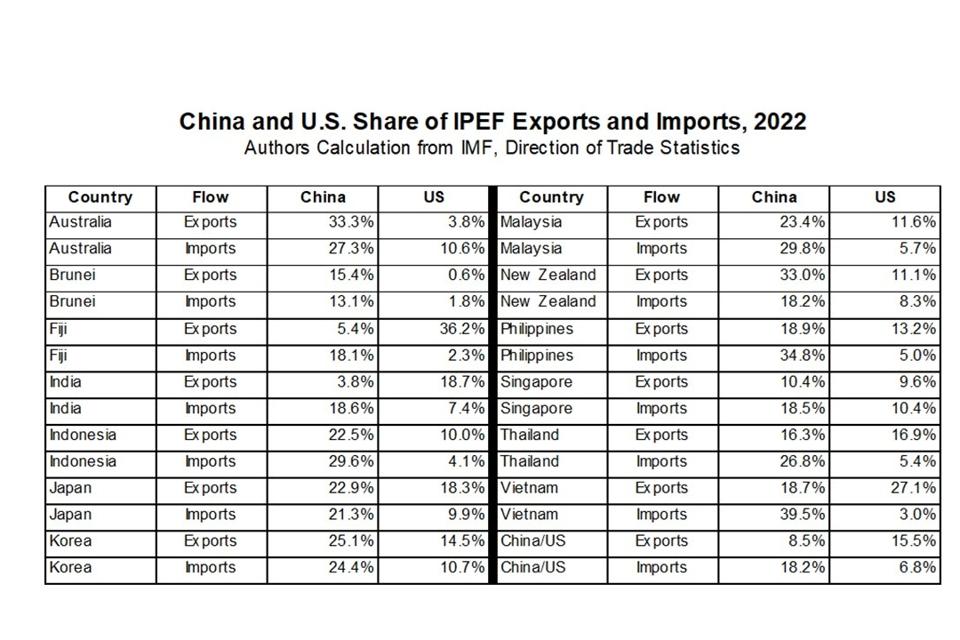

As the world’s second largest economy, surrounded by countries that together constitute the fastest growing and most dynamic region in the world, China is naturally going to be a top export market and top supplier to most of these countries. The so-called “Gravity Model” explains that trade flows are directly proportional to the GDPs of exporting and importing countries, and inversely proportional to the distance between them. As the table below illustrates, China accounts for a larger share (in most cases a much larger share) of all 13 IPEF partners’ imports than does the United States and it is a larger destination for the exports of 9 of 13 IPEF partners.

China's regional market dominance

All else equal, large economies in close geographic proximity are going to trade more than smaller and more distant countries. It is this “all else equal” part that needs to be tilted in favor of incentivizing U.S.-Indo-Pacific trade. Without the allure of better market access terms for IPEF partners, there is unlikely to be sufficient thrust to escape the gravitational pull that makes China the largest export market and source of imports to most countries in its region.

Normally, there is nothing wrong with such geographic proximity inviting regional interdependence. And, of course, the United States has Canada and Mexico as its largest partners, mostly on account of the same physics. But when interdependence becomes overdependence that can be weaponized to coerce governments into taking positions they otherwise would not, the problem goes beyond the commercial losses and opportunity costs to implicate U.S. strategic and security objectives. As China’s economic centrality has increased, many countries have been cajoled in this manner and many more remain vulnerable. As in financial management and other endeavors, the key to reducing such risk is diversification.

The Biden administration has been clear that it does not intend to negotiate new market access commitments or even to pursue traditional trade agreements. The domestic politics surrounding policies that are reflexively portrayed as favoring foreign producers over domestic workers – regardless of the truth – are too toxic and, frankly, the 2024 election may hinge on the votes of a few hundred thousand people in rust belt swing states who oppose trade.

At some point, however, U.S. policymakers will have to reconcile their aversion to building stronger ties with countries in the Indo-Pacific by putting real meat on the table with an acknowledgement that Washington made their choices for them.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment